Computational Algebra with Attention: Transformer Oracles for Border Basis Algorithms

Published:

This post accompanies our paper accepted at NeurIPS 2025: Computational Algebra with Attention: Transformer Oracles for Border Basis Algorithms

Many problems in cryptography, robotics, and optimization reduce to solving polynomial equations. Gaussian elimination handles linear systems in $O(n^3)$, but polynomial systems are another story: complexity explodes with degree, and classical algorithms burn most of their runtime on calculations that end up contributing nothing. We introduce the Oracle Border Basis Algorithm (OBBA), which uses a Transformer to predict which computations actually matter—achieving speedups of up to 3.5× while guaranteeing correctness through verified fallback.

Polynomial System Solving and Its Challenges

A polynomial system is a collection of equations like $x^2 + y^2 = 1$ and $xy = 0.5$ in several variables. The goal is to describe all common solutions. For linear systems, Gaussian elimination does this efficiently and with very little wasted work. For polynomial systems, the analogous algorithms are far more expensive: the number of candidate terms and intermediate polynomials grows exponentially, and most of them turn out to be redundant in hindsight.

Our work focuses on this redundancy. We ask whether it is possible to predict, before doing any heavy algebra, which computations are likely to be useful—and then use those predictions to steer a classical algorithm without sacrificing correctness.

Background: From Gaussian Elimination to Border Bases

To provide intuition, recall that Gaussian elimination offers a systematic route to row echelon form in linear algebra, simplifying linear systems to a point where solutions become directly accessible. The Border Basis Algorithm (BBA) [1] pursues an analogous goal in the polynomial setting, producing a border basis—a structured, canonical representation that encodes all solutions to a polynomial system.

A border basis plays a role in polynomial algebra reminiscent of row echelon form in linear algebra. Just as each row in echelon form has a distinct pivot variable, each polynomial in a border basis has a distinct leading monomial such as $x^2$. Together, these polynomials generate an ideal—the algebraic structure encoding all solutions to the original system.

Crucially, both structures are verifiable: given a candidate output, one can check whether it is valid without re-running the algorithm. This property is what enables our correctness guarantee.

One important constraint is that the BBA only applies to systems with finitely many solutions, analogous to requiring a linear system to have full rank. For instance, the system $x^2 + y^2 = 1$ and $x = y$ has exactly two solutions, whereas $x^2 + y^2 = 1$ alone has infinitely many (the unit circle) and falls outside the algorithm’s scope.

The Border Basis Algorithm

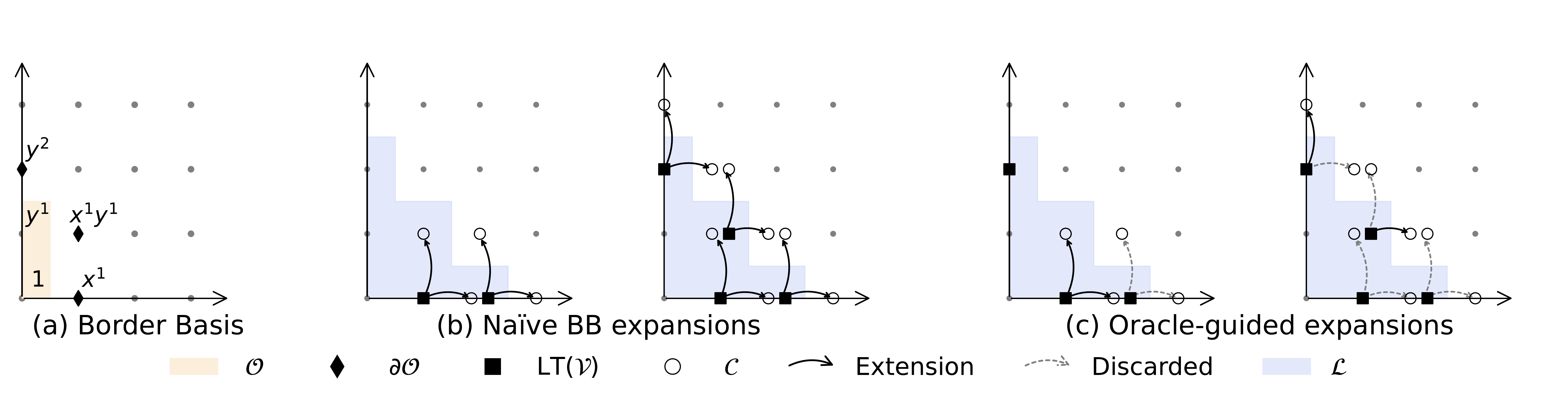

The core operation of the BBA mirrors Gaussian elimination: maintain a set of basis polynomials and systematically extend it by combining polynomials to eliminate terms. However, unlike linear systems, polynomial systems require working degree by degree—starting with low-degree polynomials, then progressively considering higher degrees until the basis stabilizes.

Since the algorithm operates degree by degree, at any given iteration we only consider polynomials up to some maximum degree $d$. This defines the current computational universe $\mathcal{L}$—the set of all monomials up to degree $d$. For example, with two variables $x$ and $y$ at degree 2, the universe is $\mathcal{L} = \{1, x, y, x^2, xy, y^2\}$. The algorithm maintains a generator set $\mathcal{V}$ of polynomials with distinct leading terms, tracking only polynomials that lie entirely within $\mathcal{L}$; terms outside this set are deferred to later iterations.

At each iteration, the algorithm proceeds as follows:

- Expansion: Multiply every polynomial in the current basis by every variable, creating a pool of candidate polynomials $\mathcal{V}^+$.

- Reduction: Apply Gaussian elimination to compute a basis for the span of all candidates.

- Filtering: Retain only those polynomials whose terms lie entirely within the computational universe $\mathcal{L}$.

A candidate polynomial extends the basis if, after reduction, it produces a non-zero polynomial that was not already expressible as a combination of existing basis elements. If it reduces to zero, it was redundant—merely a consequence of polynomials already present.

On the other hand, we call $\mathcal{V}$ an $\mathcal{L}$-stable span, if after the filtering, no polynomial is retained.

A Worked Example

Consider one iteration at degree 2, where the computational universe is:

\[\mathcal{L} = \{1, x, y, x^2, xy, y^2\}\]and the current generator set contains two polynomials:

\[\mathcal{V} = \{x - 1,\; x^2 + y^2 - 1\}\]Step 1: Expansion. Multiply each polynomial in $\mathcal{V}$ by each variable ($x$ and $y$) to form $\mathcal{V}^+$:

| Expansion | Result |

|---|---|

| $x \cdot (x - 1)$ | $x^2 - x$ |

| $y \cdot (x - 1)$ | $xy - y$ |

| $x \cdot (x^2 + y^2 - 1)$ | $x^3 + xy^2 - x$ |

| $y \cdot (x^2 + y^2 - 1)$ | $x^2y + y^3 - y$ |

Step 2: Reduction. Apply Gaussian elimination to compute a basis for the span of $\mathcal{V}^+$:

- $x^2 - x$ reduces (using $x^2 + y^2 - 1$) to $y^2 + x - 1$

- $xy - y$ cannot be further reduced

Step 3: Filtering. Retain only polynomials whose terms lie entirely within $\mathcal{L}$. The last two expansions contain $x^3$, $xy^2$, $x^2y$, and $y^3$—monomials outside the computational universe—and are therefore discarded. This yields two new polynomials that extend $\mathcal{V}$:

\[\mathcal{V} \leftarrow \{x - 1,\; x^2 + y^2 - 1,\; y^2 + x - 1,\; xy - y\}\]Of 4 candidates, only 2 were useful; the remaining 2 fell outside the current scope. This was a minimal example—as problems grow, the ratio of redundant to useful reductions becomes substantially worse. In Gaussian elimination, redundant rows reduce to zero; in border basis computation, the majority of generated candidates reduce to zero.

Computational Redundancy in the Border Basis algorithm

A linear system can be overdetermined: some equations are linear combinations of others. In Gaussian elimination, this appears as rows that reduce to zero—redundant equations that, if identified in advance, could simply be omitted.

The Border Basis Algorithm suffers from the same redundancy at a far worse ratio. The space of candidate expansions grows combinatorially, yet the survivors—polynomials that remain nonzero after reduction—are sparse. We pay the full cost of generating and reducing every candidate, only to learn that most were unnecessary.

This is precisely the inefficiency our Transformer oracle addresses.

A Neural Oracle for Expansion Selection

Rather than exhaustively expanding all candidates and discovering afterward that most reduce to zero, we predict in advance which expansions are likely to extend the basis. We train a Transformer that takes the current polynomial set $\mathcal{V}$ and monomial universe $\mathcal{L}$ as input, and outputs a subset $\mathcal{C} \subseteq \mathcal{V}^+$ of expansions predicted to survive reduction and filtering.

The Border Basis Algorithm operates degree-by-degree, so each iteration provides a natural training example: given $\mathcal{V}$ and $\mathcal{L}$, we record which expansions survived. Running the algorithm once yields a full dataset of minimal expansions.

Of course, a neural network can miss crucial expansions. But border bases are far easier to verify than to compute—so we check the result and fall back to the standard algorithm if needed. This gives us the best of both worlds:

- Accurate predictions → maximum speedup

- False positives → additional overhead from extra reductions

- False negatives → verification fails, fallback to full expansion

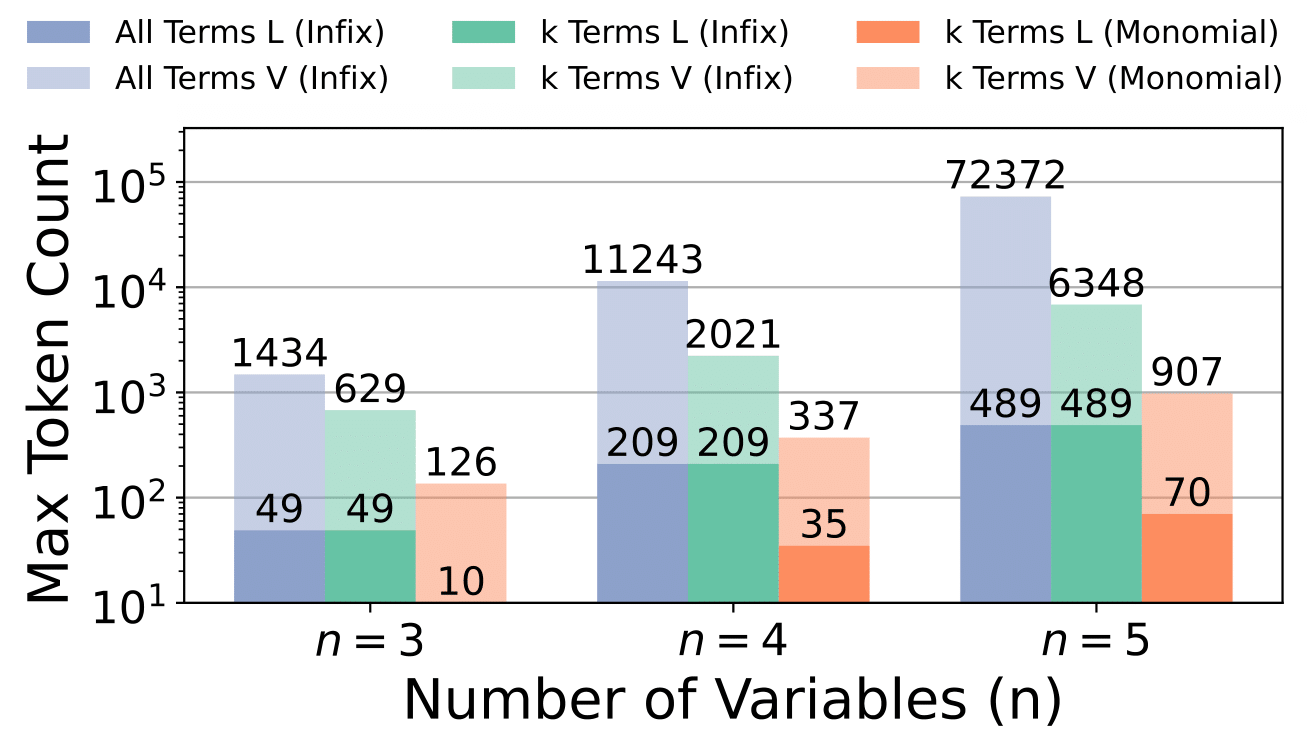

Tokenizing Polynomials

Polynomials can contain thousands of terms. A naive tokenization—one token per coefficient, one per exponent, plus operators—blows up quickly. Even $x + 2$ becomes seven tokens:

C1, E1, E0, +, C2, E0, E0

With $n$ variables, each term costs $(n+1)$ tokens. This is prohibitive.

We encode each term as a single token. Instead of breaking $3x^2y$ into separate tokens for the coefficient and each exponent, we combine everything into one embedding:

\[\text{embed}(\text{term}) = \text{embed}_{\text{coef}}(c) + \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \text{embed}_{\text{var}_i}(a_i) + \text{embed}_{\text{sep}}\]This matches how polynomial algebra actually works: operations combine terms with matching monomial structure. With one token per term, attention can directly compare terms across polynomials instead of first figuring out which token clusters belong together.

We also truncate to the first $k$ leading terms of each polynomial—these typically determine which expansions survive. Together, these choices drastically cut token count and let us handle much larger systems.

Generating Training Data

The BBA only applies to systems with finitely many solutions. Random polynomials almost never have this property—they have either no solutions or infinitely many.

We sample in reverse: start with a valid border basis (which by definition has finitely many solutions), then apply random transformations to generate diverse examples while preserving the algebraic structure.

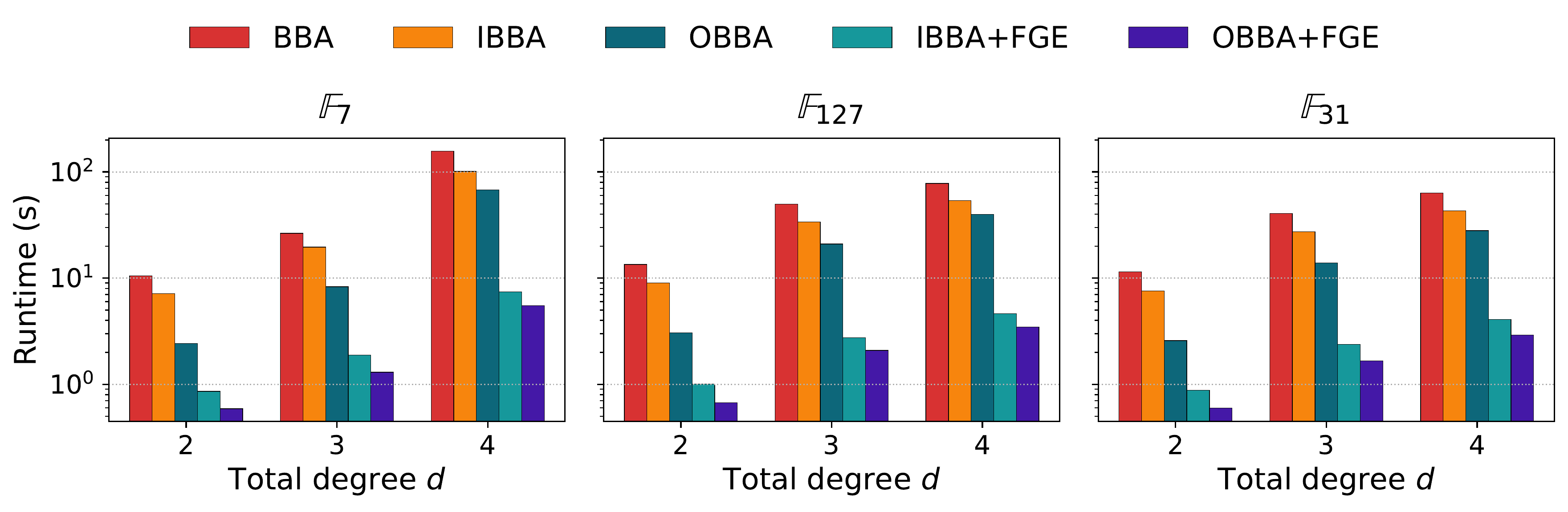

Experimental Results

We evaluate on randomly generated polynomial systems over finite fields—a setting common in cryptographic applications and algebraic coding theory. Each system has a known, finite solution set, enabling automatic verification of correctness.

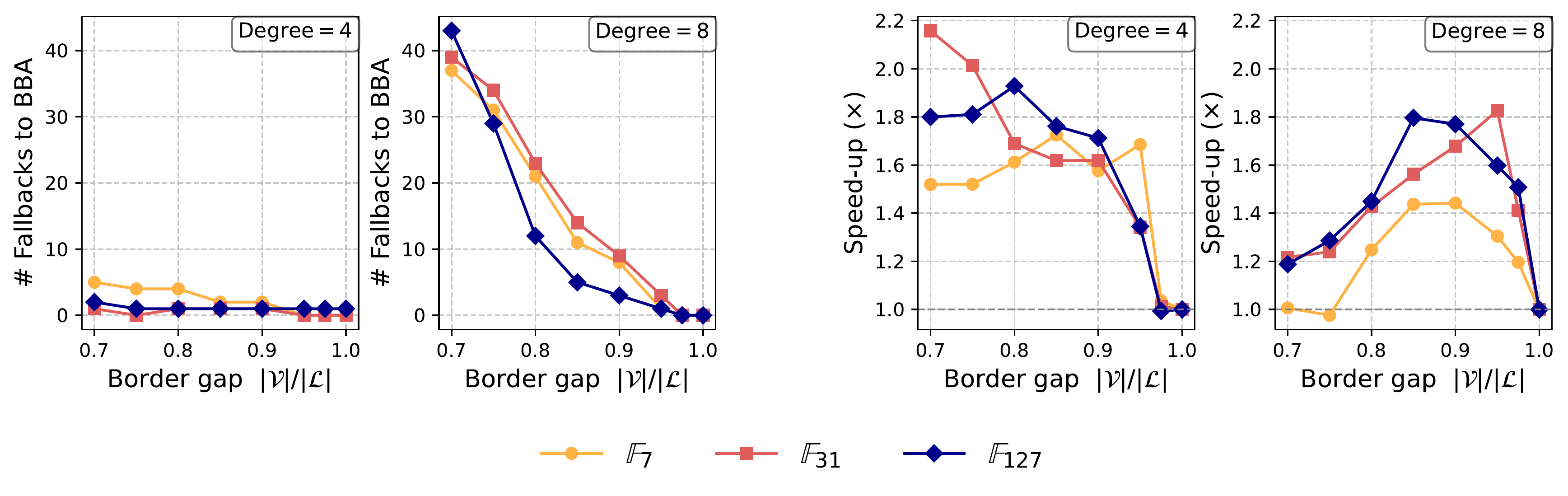

Crucially, the oracle generalizes well beyond its training distribution. Models trained exclusively on degree-2 polynomials successfully accelerate degree-3 and degree-4 problems—instances 10–100× harder than anything seen during training. This means we can generate training data cheaply by solving easy problems, then deploy the trained model on problems that are significantly harder.

Numerical Results

For 5-variable polynomial systems over $\mathbb{F}_{31}$ (a prime field commonly used in computational algebra):

| Degree | Baseline BBA | Our Method | Speedup |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 (in-distribution) | 11.4s | 0.60s | 19× |

| 3 (out-of-distribution) | 40.7s | 1.7s | 24× |

| 4 (out-of-distribution) | 136.7s | 5.6s | 24× |

The out-of-distribution results are notable: problems significantly harder than anything in training, yet the oracle still achieves greater than 20× speedup. When the oracle does make prediction errors, the verification step detects them and triggers fallback—correctness is never compromised.

What’s Missing

We only go up to 5 variables over finite fields. Scaling further will likely need larger models and different training techniques. While out-of-distribution generalization is strong, it has limits—push too far from the training distribution and the oracle starts missing expansions. The algorithm stays correct (fallback kicks in), but speedups shrink.

Looking Ahead

Polynomial systems can encode many of the hardest problems in computation: classic NP-hard problems such as MAX-CUT can be written as polynomial optimization tasks. At the same time, polynomial constraints are often far more expressive than linear ones—some feasible sets that require exponentially many linear inequalities admit succinct descriptions with only a few polynomial equations. By designing a tokenizer that exploits this algebraic structure, we obtain highly compressed representations that fit within Transformer-scale context windows.

This approach extends in principle to polynomial optimization and numerical root-finding—tools that play central roles in robotics, computer vision, and combinatorial optimization. The general pattern is to use learned predictions to guide and prune a classical algorithm’s search, while retaining a fast verification step so that any accepted solution comes with a clear correctness certificate. Border bases are a clean first testbed. The more interesting story is broader: wherever a hard problem has a compact algebraic encoding and a fast verifier, there’s an opportunity to drop in a learned oracle.

Paper: Computational Algebra with Attention: Transformer Oracles for Border Basis Algorithms (NeurIPS 2025)

Code: github.com/HiroshiKERA/OracleBorderBasis

@inproceedings{kera2025computational,

title={Computational Algebra with Attention: Transformer Oracles for Border Basis Algorithms},

author={Hiroshi Kera and Nico Pelleriti and Yuki Ishihara and Max Zimmer and Sebastian Pokutta},

year={2025},

booktitle={Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS)},

eprint={2505.23696},

archivePrefix={arXiv},

primaryClass={cs.LG},

url={https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.23696},

}

References

[1] Kehrein and Kreuzer. Computing border bases. Journal of Pure and Applied Algebra, 205(2):279–295, 2006.